When cyclists think about climbing power, internal hip rotation strength is not even a topic of conversation. Leg strength, VO2 max, and power-to-weight ratios take precedence. Yet hip rotation strength is a critical component of pedaling biomechanics that remains overlooked even in most training programs. While many riders focus on the major muscle groups that drive the pedals downward, the subtle rotational forces at the hip joint play a surprisingly significant role in power transfer, pedaling efficiency, and injury prevention on steep gradients. This often-neglected aspect of cycling performance can be the difference between struggling up climbs and powering through them with improved efficiency. Understanding and developing hip internal rotation strength may unlock gains that traditional training approaches miss entirely.

In this post, we break down what the hip internal rotation is, exercises to strengthen this area, and what to pay attention to to improve your cycling performance.

PEDAL MY WAY NEWSLETTER

Weekly training tips, cycling strategies, and fitness insights for sustainable performance.

No spam—just actionable guidance to help you train smarter.

Table of Contents

Understanding Hip Internal Rotation

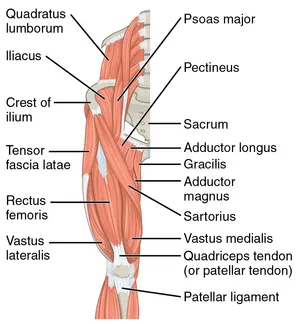

Hip internal rotation is the rotational movement of the femur (thigh bone) toward the midline of the body when the hip is flexed. Imagine sitting in a chair and rotating your knee inward—that’s hip internal rotation. In anatomical terms, this movement occurs in the transverse plane and is primarily controlled by muscles including the gluteus medius and minimus (anterior fibers), tensor fasciae latae, and the adductor group.

Most people can achieve roughly 30-45 degrees of passive hip internal rotation, though this varies considerably based on individual anatomy, training history, and hip socket structure. What matters for cycling performance isn’t just the range of motion available, but the ability to control and generate force through this movement pattern. The hip joint operates as a ball-and-socket joint, allowing movement in multiple planes simultaneously, and during the pedal stroke, subtle internal rotation occurs continuously as the leg moves through its circular path.

Hip Internal Rotation in Cycling Biomechanics

During the pedal stroke, hip internal rotation works in concert with hip flexion and extension to create smooth, efficient power transfer. As the leg moves from the top of the pedal stroke through the power phase, the femur undergoes slight internal rotation to maintain optimal alignment with the pedal spindle. This rotational component becomes even more pronounced during climbing when riders adopt a more forward hip position and increased hip flexion angles.

When climbing out of the saddle, hip internal rotation strength becomes critical for stabilizing the pelvis and preventing excessive lateral movement. Each pedal stroke requires the stance leg to control rotational forces while the opposite leg drives downward. Weak hip internal rotators can lead to compensatory movement patterns—the knee may collapse inward (valgus), the foot may pronate excessively, or the pelvis may drop on the non-weighted side. These compensations not only waste energy through inefficient force vectors but also increase stress on the knee and lower back.

The kinetic chain in cycling demands that force generated by the large gluteal and quadriceps muscles be transmitted efficiently through a stable hip joint. Hip internal rotation strength provides this stability, acting as a crucial link that prevents power leakage and maintains optimal joint alignment throughout the demanding repetitive motion of climbing.

Research on Hip Internal Rotation and Cycling Performance

While research specifically examining hip internal rotation strength in cyclists is limited compared to studies on other muscle groups, emerging evidence from biomechanics and sports medicine highlights its importance. Studies on lower limb kinematics in cycling have demonstrated that hip rotation patterns significantly influence knee alignment and pedaling efficiency. Research has shown that cyclists with poor rotational control at the hip often display greater knee valgus angles, which correlates with reduced power output and increased injury risk.

Research from running biomechanics provides relevant insights, as hip internal rotation strength has been directly linked to improved performance and reduced injury rates in endurance athletes. Given the similar demands of repetitive hip flexion and extension in both sports, these findings likely translate to cycling. Studies have identified that athletes with stronger hip internal rotators demonstrate better control of the femur during high-load activities, resulting in more efficient force transmission through the kinetic chain.

Biomechanical analyses of elite cyclists have noted that superior climbers often maintain tighter, more controlled hip mechanics with minimal extraneous movement. While these studies don’t always isolate internal rotation specifically, the stable hip patterns observed suggest strong rotational control. The gap in cycling-specific research represents an opportunity for riders to gain competitive advantages by applying principles already established in related endurance sports.

Mobility vs Strength

A critical distinction often missed in training programs is the difference between hip internal rotation mobility and hip internal rotation strength. Many cyclists discover they have adequate passive range of motion when lying on a treatment table, yet lack the neuromuscular control and strength to utilize that range effectively under load during the pedal stroke.

Mobility refers to the available range of motion at a joint—how far the hip can internally rotate when moved passively. Strength, conversely, is the ability to actively control and generate force throughout that range. You can possess excellent mobility but still have weak internal rotators that fail to stabilize the hip during the intense demands of climbing. This explains why some riders with good flexibility still experience biomechanical inefficiencies and pain.

For cycling performance, strength through the functional range is more valuable than extreme mobility. A rider who can actively control 30 degrees of hip internal rotation under load will climb more efficiently than someone with 50 degrees of passive mobility but only 15 degrees of active, controlled strength. The goal should be developing strength that matches or slightly exceeds your mobility, creating a stable, powerful hip complex capable of handling the demands of sustained climbing efforts.

Training Exercises for Hip Internal Rotation Strength

Developing hip internal rotation strength requires targeted exercises that load this specific movement pattern. Here are proven exercises to incorporate into your training routine:

Seated Hip Internal Rotation with Resistance Band: Sit on a bench with a resistance band looped around one foot and anchored to the side. With your knee bent at 90 degrees, rotate your foot outward (which internally rotates the hip) against the band resistance. Perform 3 sets of 15-20 repetitions per side, focusing on controlled movement without allowing the pelvis to shift.

90/90 Hip Lifts: Sit on the ground with one leg in front bent at 90 degrees (hip externally rotated) and the back leg also at 90 degrees (hip internally rotated). Lift the knee of the back leg off the ground using hip internal rotation strength while keeping the pelvis stable. Hold for 2-3 seconds and repeat for 10-12 repetitions per side.

Single-Leg Romanian Deadlift with Rotation: This exercise combines hip hinge mechanics with rotational control. Stand on one leg and perform a Romanian deadlift while holding a light weight. As you return to standing, add a slight internal rotation of the stance hip. This builds functional strength in the climbing position.

Clamshells with Internal Rotation Emphasis: While traditional clamshells target hip external rotation, you can modify them by lying on your back with knees bent and feet together. Keep feet touching while internally rotating one hip to bring that knee toward the midline against band resistance. This directly targets the internal rotators.

Copenhagen Plank Progression: While primarily an adductor exercise, Copenhagen planks also engage hip internal rotators significantly. The adductor group works synergistically with internal rotators to stabilize the hip during climbing.

Integrate these exercises 2-3 times per week during your strength training sessions. Start with bodyweight or light resistance and progress gradually, prioritizing movement quality over load. These exercises complement rather than replace traditional cycling-specific strength work. Here are some workouts for total body strength and conditioning.

How Hip Internal Rotation Improves Climbing Power

The connection between hip internal rotation strength and climbing power operates through several mechanisms. First, improved rotational control minimizes energy-wasting compensatory movements. When your hip internal rotators properly stabilize the femur throughout the pedal stroke, force travels efficiently from your glutes and quads directly into the pedals rather than dissipating through excessive knee or pelvic movement.

Second, stronger hip internal rotators contribute to better knee tracking. Optimal knee alignment over the pedal maximizes the effectiveness of your quadriceps and reduces the mechanical disadvantage caused by valgus collapse. This means more of your muscular effort converts directly into forward propulsion up the climb.

Third, hip internal rotation strength enables you to maintain proper position during long climbs without excessive fatigue. As climbs extend beyond several minutes, fatigue-induced form breakdown typically manifests as collapsing knees and unstable hips. Riders with robust rotational strength maintain their biomechanics longer, preserving power output when others begin to fade.

Finally, strong hip internal rotators allow for more aggressive out-of-saddle climbing. When standing on the pedals during steep pitches, the demands on hip stability increase dramatically. The ability to control rotation while generating maximum power lets you attack climbs more effectively and respond to accelerations without compromising form.

Injury Prevention and Longevity

Beyond performance benefits, hip internal rotation strength plays a crucial role in injury prevention and extending your cycling career. Many common cycling overuse injuries can be traced back to poor hip stability and rotational control. Patellofemoral pain syndrome, iliotibial band syndrome, and lower back pain often develop when compensatory movement patterns place excessive stress on structures that aren’t designed to handle rotational forces.

Weak hip internal rotators create a cascade of biomechanical issues. The knee may track improperly, increasing stress on the patellar tendon and cartilage. The IT band must work overtime to stabilize a hip that should be controlled by the gluteal muscles. The lower back compensates for pelvic instability with excessive movement and muscle tension. Addressing hip internal rotation strength can resolve these patterns before they develop into chronic problems.

For masters athletes and long-term cyclists, maintaining hip internal rotation strength becomes increasingly important. Age-related changes in muscle mass and connective tissue can reduce rotational stability, making intentional strength work essential for continued performance and injury-free riding. Investing in hip rotational strength now pays dividends in sustained cycling ability for decades.

The repetitive nature of cycling—thousands of pedal strokes per ride—means that even small biomechanical inefficiencies compound into significant tissue stress over time. Strengthening hip internal rotators creates a more resilient system capable of handling high training volumes without breaking down.

Integrating Hip Internal Rotation Into Training

Successfully incorporating hip internal rotation work into your training requires thoughtful planning rather than simply adding more exercises randomly. The key is viewing this strength work as an integral component of your cycling preparation, not an optional extra.

Schedule hip internal rotation exercises during your strength training sessions, ideally 2-3 times per week during base and build phases. These exercises work well as part of a comprehensive hip and core strengthening routine. Perform them when you’re relatively fresh rather than after exhausting rides when movement quality suffers. Many riders find success doing this work on easy training days or as part of their warm-up before moderate-intensity rides.

During competition phases, maintain hip internal rotation strength with reduced volume—perhaps one focused session weekly. The goal shifts from building strength to preserving the gains you’ve developed. Maintenance work requires less volume but should maintain intensity and movement quality.

Consider periodizing your hip strength work similarly to your on-bike training. During the off-season, emphasize building foundational strength with higher volume and progressive overload. As you move into specific preparation periods, reduce the volume of strength work while maintaining the neuromuscular patterns through targeted exercises that more closely mimic the demands of climbing.

Pay attention to how your body responds. Some riders notice improved climbing power within 3-4 weeks of consistent hip strengthening, while others require 6-8 weeks to develop meaningful neuromuscular adaptations. Be patient and trust the process—biomechanical improvements often precede noticeable performance gains.

Monitoring Progress and Assessment

Tracking improvements in hip internal rotation strength requires both subjective feedback and objective measurements. Start by establishing baseline assessments that you can periodically retest to gauge progress.

For a simple self-assessment, perform the seated hip internal rotation test. Sit on a bench with your knee bent at 90 degrees and your foot flat on the ground. Have someone measure how far you can actively rotate your foot outward (internal hip rotation) while keeping your pelvis stable. Record this measurement in degrees or simply note a reference point. Retest every 4-6 weeks.

Functional assessments provide valuable feedback on how strength translates to cycling performance. Video your pedal stroke from the front during climbing efforts, both seated and standing. Look for excessive knee valgus, hip drop, or lateral swaying. As hip internal rotation strength improves, these compensatory patterns should diminish. Compare videos taken at monthly intervals to track changes in movement quality.

On-bike metrics can indicate improvements indirectly. Monitor your ability to maintain power output during long climbs, particularly in the final minutes when fatigue sets in. Stronger hip rotational control often manifests as better power sustainment in fatigued states. Track your perceived exertion at given power outputs on familiar climbs—improved efficiency may allow the same power to feel easier.

Subjective markers matter too. Notice whether you experience less knee or hip discomfort during and after long climbing sessions. Pay attention to whether you can hold your position longer when standing on climbs without feeling unstable. These qualitative improvements often appear before quantitative performance gains show up in your data.

Consider periodic professional biomechanical assessments if accessible. A qualified bike fitter or physical therapist can provide detailed analysis of your hip mechanics and offer specific feedback on how your strength work translates to pedaling efficiency.

Unlocking Your Climbing Potential Through Hip Strength

The path to better climbing power doesn’t always require more intervals, more miles, or even more weight loss. Sometimes the key lies in addressing the subtle biomechanical factors that separate efficient climbers from those who struggle. Hip internal rotation strength represents one of these hidden leverage points—a relatively small investment of training time that can yield disproportionate returns in climbing performance, efficiency, and injury resilience. By understanding the role of hip internal rotators in stabilizing your pedal stroke and controlling the kinetic chain, you gain insight into why some riders seem to float up climbs while others grind. When your hips provide a stable, controlled platform for your major muscle groups to work from, every watt you generate translates more effectively into forward momentum.

Hip internal rotation strength is a piece of that puzzle that too many cyclists overlook. By addressing it now, you’re building a foundation for sustained climbing performance that will serve you for years to come, giving you the hip strength and stability to power through challenging climbs with newfound confidence and efficiency.

Happy Climbing!

Related Cycling and Training Content

For further cycling and training tips, you can also listen to the Ask The Pedalist podcast, where we discuss common cycling topics.